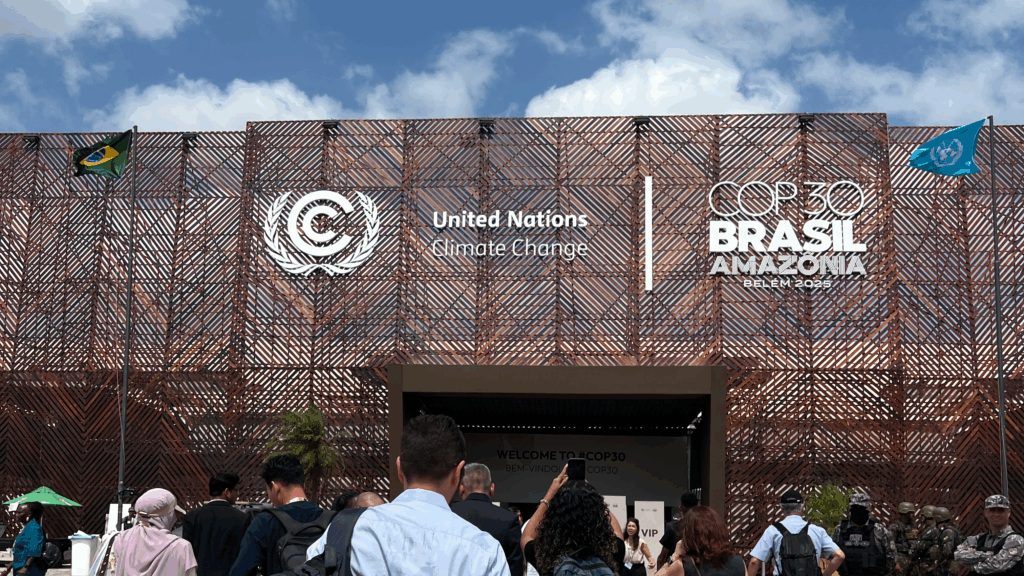

COP30 Outcome Statement: Feminist Power Delivered — But the Process Failed to Meet the Moment

The Women and Gender Constituency welcomes key outcomes from Brazil, but the process continues to fall short of the ambition demanded by frontline communities, from the mountains, forests, islands, and favelas of Latin America and the Caribbean to every region where women, Indigenous Peoples, Afro-descendant peoples, and gender-diverse defenders are safeguarding life and biodiversity. Their hopes, solutions, and resistance remind us that incremental progress is not enough. The world needs a transformation rooted in justice.

Topline Analysis of Key Outcomes

Belém Gender Action Plan (GAP)

The Belém Gender Action Plan, secured through years of coordinated and persistent advocacy by the WGC alongside key country and institutional allies, reflects both advances and losses that will shape the next nine years of gender-responsive climate action under the UNFCCC. While an intersectional lens is retained, it appears only as a diluted reference to “multidimensional factors” across activities, which is a missed opportunity to explicitly recognize gender-diverse people. Foundational human rights language, which anchors the Lima Work Programme on Gender in its preambular text, was removed from this sister mandate, reflecting the broader global backlash against rights.

In resourcing the GAP, the outcomes on Guidance to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) does have an important provision linking it to the Belem Gender Action Plan, which we look forward to operationalizing further with the adoption of a new GCF Gender Action Plan in 2026. We hope to use the references to direct access to continue to push for the GCF’s more comprehensive understanding of what that means for ensuring gender-responsive action and implementation. This is progress, but continued lack of clarity on access, combined with the chronic underfunding across the Convention, risks leaving the GAP without the means necessary for real implementation.

Positively, the text contains meaningful gains that the Women and Gender Constituency and allies fought to secure. With 27 activities, the Plan provides multiple pathways for strong implementation, including at the national level. It explicitly recognizes several structurally excluded groups, mandates the development of guidelines to protect and safeguard women environmental defenders, and creates space to address care work, health, and violence against women through national submissions and other emerging issues. Gender and age disaggregated data are integrated throughout the framework. The GAP also strengthens coherence across the Rio Conventions, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and the wider architecture of UNFCCC bodies and processes. While the absence of clear indicators weakens accountability, the Plan does establish voluntary national reporting through existing mechanisms, including Biennial Transparency Reports.

Ultimately, the strength of this document depends on how we choose to carry it forward. The Belém GAP embodies the tireless and collective work of the Women and Gender Constituency. It now becomes a cornerstone for the next decade of feminist climate advocacy, and it is a tool we must continue to defend and advance together.

Just Transition

The decision in Belém to mandate the establishment of a Just Transition Mechanism is a meaningful step forward and reflects the consistent pressure of feminists, trade unions, youth, and environmental justice groups who have insisted that just transitions must be people-centered and rights-based. While the mechanism itself is still to be designed, the mandate acknowledges the need for inclusive governance, social dialogue, and the participation of workers, Indigenous Peoples, communities, and those most affected by the transition, including through respect for Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Feminists in the Women and Gender Constituency have been central to securing this mandate. Our advocacy has emphasized that just transitions must confront inequality, protect human rights, recognize care work and social protection, and address the realities of informal and precarious labor. The decision reflects some of these priorities, even as it falls short on finance and does not address structural barriers such as debt, extractivism, or corporate influence.

Looking ahead, our vision is for a mechanism that delivers real support for communities, strengthens public and community-led solutions, and ensures transitions that are equitable, participatory, and grounded in dignity and justice. The mandate is only a starting point. Its impact will depend on whether the mechanism is designed and governed with the full involvement of feminist, labor, Indigenous, and frontline movements, who will continue to insist on a seat at the table.

Finance

The outcomes on the many finance texts do not represent new steps forward, but establish work programmes and dialogues, recall previous commitments with no new accountability, and generally keep the multilateral climate funds in operation — with a few key caveats — within a context of continued under-delivery of climate finance. We came to COP30 demanding developed country Parties fulfill their obligations to provide climate finance to developing countries in accordance with Article 9.1, including by setting a new goal on adaptation finance in alignment with the suite of adaptation items considered here. This expectation has been largely unfulfilled.

Instead, we leave without meaningful action on Article 9.1 — just with a two-year work programme talkshop on all of Article 9, but without prioritized focus on provision promised in the Mutirão decision. We also walk away with only a vague, untransparent promise to triple adaptation finance by 2035 as part of the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) efforts, but without clarity on the base-year (noting that whatever will be delivered will be way below the USD 120 billion annually by 2030 that feminists and developing countries had asked for coming to Belém). The compromise reached in the Mutirão decision also lacks a clear commitment to developed countries providing public, grant-based, non-debt-creating adaptation finance, but is instead linked to broader mobilization efforts under the NCQG. Existing commitments to developed countries’ obligations to provide climate finance were also weakened over the course of negotiations in language in the guidance texts to various multilateral climate funds.

Adaptation

Gender-responsiveness and cross-cutting commitments in the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) can only translate into real resilience when paired with strong means of implementation, especially finance, that reaches the communities who need it most, particularly women in all their diversity, who drive adaptation on the ground.

While we welcome the visibility of gender within the indicators, their current form remains largely unusable for measurement. This is a gap that can and must be corrected, so that the Belém-Addis Vision becomes an opportunity for meaningful refinement rather than a series of dialogues whose purpose is unclear.

We note with concern that the Mutirao text does not deliver the robust adaptation and adaptation finance commitments that are urgently needed. Similarly, the lack of reinforced means of implementation language in the NAPs, and the absence of clear support for GCF readiness, leaves developing countries without the support required for NAP formulation and implementation. As WGC, we will continue to engage constructively to ensure the gaps in the GGA indicators can be filled and become a starting point for gender-just adaptation outcomes.

Technology

As anticipated, technology negotiations were intense and left us with mixed feelings. Once again, Parties failed to reach an agreement on the linkages between the Technology Mechanism and the Financial Mechanism. Without decisive action to bridge the gap between technology and finance, we risk leaving developing countries without the tools they need to confront the climate crisis. We cannot build a just and sustainable future with fragmented mechanisms and postponed decisions. The technology commitments cannot afford another year of inaction.

For the second consecutive year, Parties did not welcome the Joint Annual Report, which provides a comprehensive account of the activities undertaken by the Technology Executive Committee (TEC) and the Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN) throughout the year. This raises a critical question: if Parties cannot reach consensus on receiving an activity report and continue to postpone decisions on collaboration between the two mechanisms, how can we ensure just, inclusive, and environmentally responsible climate technology development and transfer? The inability to welcome the Joint Annual Report sends a troubling message regarding Parties’ trust and support for the TEC and the CTCN, the bodies responsible for climate technology development and transfer in developing countries.

We welcome the renewal of the Technology Implementation Programme (TIP) for ten years, and particularly commend the inclusion of direct and specific language on gender-responsiveness and strengthening women’s equity within the TIP. Further delays to this process would have been a deeply disappointing outcome, as it would have hindered the implementation of other related decisions. We cannot speak of ambition or call upon developing countries to enhance their targets without providing the means of implementation and the capacity to do so. Nevertheless, ambition remains constrained, with TIP activities subject to the availability of resources rather than clearly defined financial responsibilities.

We also appreciate the agreement on the renewal of the CTCN, which includes specific language on gender-responsive technologies. This was a crucial outcome to ensure the sustainability of the Climate Technology Centre and Network, the implementing body of the Technology Mechanism. The CTCN’s work in supporting developing countries with climate technology transfer and development must be recognized and strengthened. However, the CTCN will face increasing challenges in fulfilling its mandate without clear cooperation arrangements with the Financial Mechanism.

Global Stocktake (GST) — Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) Linkages and the Global Mutirão Belém Package

The outcome text of the GST2 falls short of establishing a participatory, inclusive, and justice-oriented process. Despite widespread recognition that non-Party stakeholders are essential agents of climate ambition and implementation, the decision does not sufficiently operationalise their engagement. This represents a missed opportunity to embed transformative, community-led, and gender-responsive approaches at the heart of the GST cycle. A stronger framework is needed to ensure that GST2 actively integrates the knowledge, priorities, and innovations of frontline constituencies.

The weakening of participation and gender-responsive language compared with COP28 represents a backward step at a moment when global ambition demands the opposite. Because Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are informed by the GST, any dilution in inclusiveness upstream will translate into less equitable, less effective national climate commitments downstream. Ensuring that GST2 embeds systematic participation of grassroots, frontlines communities, including women environnmental and human rights defenders, as well as rightsholders constituencies, is essential for ensuring that NDCs reflect lived realities, community-driven solutions, and gender-just climate action.

Non-Party stakeholders are fundamental to the implementation of the Paris Agreement. The recognition of their role is stressed in the Mutirão cover decision; however, vigilance is needed regarding which business and financial actors are invited to shape processes and outcomes. Inclusion must prioritise those whose rights, territories, and livelihoods are most affected by climate impacts. The coupling of IPCC science with equity principles is particularly important here, signalling that climate action must be both evidence-based and justice-aligned.

WGC Members Quotes

“The power of our people is alive in the UNFCCC process. Two years ago, a long-term mandate on the Gender Work Programme was only a dream, yet we delivered it in Baku. A Gender Action Plan that names and recognizes the multidimensional factors shaping climate injustice, that protects women environmental defenders, and that strengthens coherence at national level for real impact felt impossible, feminist power delivered it in the halls of Belém. A year ago, a call for just transitional institutional arrangement was treated as fantasy, people’s power made it real today in Belém. As we leave here with collective pride in the victories won, we know that the true power is not in the decisions alone, but in how those decisions illuminate our struggle and our strength. And we are not done. We will return to these halls to fight for our RIGHTS. We will return to end the culture of trading our rights as bargaining chips. Our feminist power, our people’s power will win the Human RIGHTS fight.” – Mwanahamisi Singano, Director of Policy, WEDO

“Having the Gender Action Plan delivered in Belém, in the heart of the Amazon, is deeply symbolic and politically significant. It reminds us of the power of the people who protect biodiversity and territories, who stand firmly against extractivism, militarization, and the financing of destruction that threatens both communities and ecosystems. Securing this outcome in a world marked by rising conservatism is important, but feminists demand much more. From Rio 92 to COP30 in Belém, we have fought for environmental, social, and economic justice, and we did not come here only to resist rollbacks. We came to imagine a different model of climate governance that places rights, care, and community wisdom at the center. We will stay united to demand a just transition built on care, consent, and sovereignty, and to insist that climate finance becomes a true instrument of justice and reparation that transforms lives instead of serving markets.” – Michelle Ferreti, Codirector, Instituto Alziras

Just Transition: “Feminists have made it very clear: this process must deliver, failure is no longer an option. The Belem Action Mechanism (BAM) emerges as a call made by feminists, trade unions, environmental organizations, and youth that have demonstrated the vitality of being at the table contributing to the transition we are all calling for. The creation of the BAM is a key to policy coherence; it is a bold step needed to take climate cooperation to a level that delivers for the people; it is the ambition we have been hearing so much in the rooms over the past years. Feminists have been a crucial powerhouse in the conception of the BAM. We will continue firmly standing for our rights. We will closely monitor the process to establish a BAM that benefits the population and moves us toward the implementation of the commitments agreed upon in Paris” – gina cortés valderrama, WGC Just Transition Working Group Co-Coordinator

“Today, feminists rejoice. In the Belem Gender Action Plan, we have a framework of 27 activities that can lead to action that centers gender justice. The efforts of the Women & Gender Constituency are evident here, in such concrete wins – from guidelines on women environmental defenders to key entry points to care, violence against women and health and avenues, activities that enhance coherence across negotiations streams and bodies and that drive national-level implementation. In a moment when we seem to be losing so much, there is so much beauty in the collective work that drove so much of the advocacy around the GAP, and in this final result. This GAP, however, will only be effective hand-in-hand with other essential advancements, including by securing a gender-just transition and the provision of finance, and the continuous integration of an intersectionality framework across the UNFCCC. There is a long way to go, and so much we could say could be better, but today, today we celebrate!” – Claudia Rubio Giraldo, Policy Coordinator, WEDO

Mitigation: “Thousands of women and gender-diverse people alongside a critical mass of countries were pushing for a Fossil Fuels phase out pathway at COP30, not only because of the historic responsibility of fossil fuels in the climate crisis but also because they are at the root of gendered inequalities and sexual violence. Neither did the Mutirão process nor the Mitigation Work Program delivered in that sense, but we’re glad that Brazil announced an international roadmap to report back at the conference in Colombia in April, even if not legally bindingThe one bright spot: Indigenous Peoples and their knowledge, as well as informal workers, many of which are women, receive long-overdue recognition in the Mitigation Work-Program. But real progress demands that gender justice be treated as essential and explicit, not as optional.” – Alba Saray Pérez Terán, Climate Change Policy Advisor

“It’s encouraging that 89% of new NDCs now mention gender – governments are finally putting women and gender-diverse people on the climate page. But those same NDCs stay silent on the core driver of the crisis: fossil fuel production. A genuine ‘transitioning away’ pathway means clear, quantitative targets to cut fossil fuel production in line with 2030 ambition. No country has yet put those numbers on the table. Without explicit production phase-out targets, we are still sketching around the problem instead of dismantling it.” – Shruti Sharma, Lead for Affordable Energy, International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD)

Finance: “Seeing these negotiations end with talkshops and reminders for Parties to fulfill their existing commitments without either a real delivery plan or any real money on table since adopting the new collective quantified goal just one year ago in Baku further entrenches the betrayal and disappointment we felt with that abhorrent decision. As a whole, the finance texts decided at COP30 are a deeply inadequate response given our reality of climate catastrophe and the established science and legal mandate – through the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement and reinforced recently with the International Court of Justice’s advisory opinion – for Parties to act, and for developed country Parties to provide climate finance. We need gender-responsive climate finance to deliver climate action in ways that do not further entrench inequality and injustice but strengthen the work of gender-just climate solutions already being implemented worldwide, enable countries to devote resources to resilience instead of debt service, and ensure all climate action – from adaptation to mitigation to addressing loss and damage – is designed, implemented, and monitored with the expertise and meaningful inclusion of women, girls, and gender-diverse people.” – Tara Daniel, Associate Director, Policy, WEDO

“Gender-responsiveness of climate finance stands and falls first and foremost with a scaling up of new, adequate and predictable public non-debt creating climate finance provided by developed countries to developing countries as a matter of their legal obligations under the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement. It is not just a matter of quantity, but of quality in ensuring access, centering human rights and a focus on the needs and priorities of those most impacted by climate change. Judged by this standard, the climate finance outcomes from COP30 in Belém failed women and girls and gender-diverse people and continued the slippery slope of undermining climate justice and equity begun with the adoption of the NCQG last year in Baku. A vague promise to triple adaptation finance by 2035 lacks a base year and fails to mention both its quality and who will deliver it. Developed countries dodging their responsibilities on all fronts continue their accelerated pull-back from their finance provision obligations here in Belém, expecting the private sector miraculously to step in where they fail, at a time when trust in the multilateral climate regime needs their increased contributions to raise collective ambition.” – Liane Schalatek, Associate Director, Heinrich Böll Foundation Washington, DC

Global Stocktake: “We deeply regret that parties agreed on a bare minimum text that does not lead to decisive action, and that they have missed an opportunity to open the GST 2 process to meaningful contribution of non-Party stakeholders, including rightholders, Indigenous Peoples and frontline communities, women and girls in all their diversities, who lead on climate action and can bring the transformative approach that we desperately need for an ambitious and just transition.” – Anne Barre, WECF

GST and NDC-Mutirão: “After two years of negotiations still we struggle to achieve fair inclusion of participation language with a gender responsive approach. The GST decision text as well as the Global Mutirao Belem package have weaker gender language than the cover decision of GST 1 from COP28 in Dubai. In addition, because NDCs are shaped by the GST, the GST must fully include diverse civil society and grassroots voices—Indigenous Peoples, women and gender-diverse people, and persons with disabilities—to ensure just and effective climate solutions We remind the parties and the presidency that bottom- up and grassroots participation with a clear gender responsive approach in all GST processes, brings not only more credibility and equity, but also greater climate ambition — which is what we expected from this COP of the Truth.” – Floridea Di Ciommo, Director at cambiaMO, changing MObility

Technology: “What would mitigation, adaptation, or just transition look like without climate technology reaching developing countries? While we welcome the renewal of the TIP and the CTCN review, the persistent inability to agree on technology-finance linkages and to welcome the Joint Annual Report undermines the ability of developing countries to access the capacity and tools needed to implement ambitious climate action.” – Valeria Peláez Cardona, Programme Coordinator, WECF